Palliative and End of Life Care

Introduction

Providing high-quality palliative care specific to the needs of individuals at the end of life and their families is imperative. The nursing community at the Wales Home is showing its commitment to and passion for excellence in nursing care by applying this program called “End of Life Care During the Last Days and Hours”. The program is a modified version of the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2011), who has implemented the guideline End of Life Care During the Last Days and Hours (Best Practice Guidelines, www.rnao.org).

The Wales Home is building its capacity to ensure that end of life care is accessible to all residents, with the exception of sudden death individuals. A person with life-limiting illness and/or their family members with end-stage disease, frailty, or terminal illness are identified as potentially benefiting from end-of-life care.

1. Context

Nurses and professionals find caring for individuals during the last days and hours of life challenging and most of them feel ill-prepared to provide end-of life care.

Palliative care is both a philosophy and an approach to care. A palliative approach to the care of people facing a life-limiting disease is the common philosophical basis. (see terminology Annex 1)

WHO (2002) defines palliative care as an approach to care that aims to “improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illnesses, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” (p.14).

2. EOL Trajectories & Care

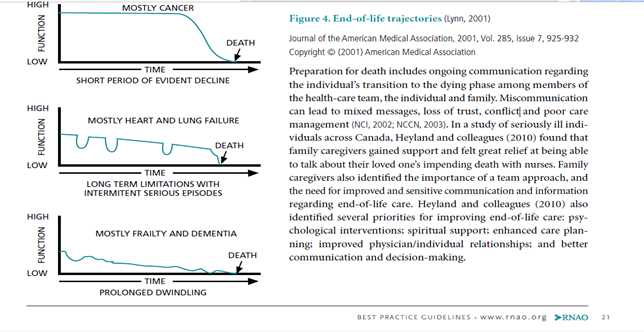

End-of-life trajectories (Figure) can assist clinicians in identifying individuals who may benefit from hospice palliative care. The trajectories show three typical patterns of decline for individuals with cancer, chronic illness and frailty:

- For most cancers there is a short period of obvious decline leading to death;

- The trajectory for patients with chronic organ failure is characterized by long-term disability with periodic exacerbations and unpredictable timing of death;

- For those with frailty and dementia, the pattern is characterized by a slow dwindling course to death.

Ferris, FD., Balfour, HM., Bowen, K., Farley, J., Hardwick, M., Lamontagne, C., Lundy, M., Syme, A. West, P. A (2002) summarized the EOL scenario as a model of care.(Ferris et coll (2002), Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care.(Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association,)

The term end of life care refers to the care that is provided to a client at the end of his or her life. The goal of end of life care is to improve the quality of living and dying, and minimize necessary suffering. It encompasses the physical, spiritual, social, psychosocial, cultural, and emotional dimensions of client care.

While palliative care can be a component of end of life care, end of life care also includes aspects that are beyond the scope of palliative care, such as advance care planning.

Within the palliative care philosophy, death is viewed as a normal process; thus, the aim of palliative care is to neither hasten nor postpone death.

3. Palliative Care

Palliative care aims to relieve client suffering and improve the quality of living and dying. It strives to help clients and families address physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical issues, and their associated expectations, needs, hopes, and fears. Palliative care prepares the client and others for managing self-determined life closure and the dying process. Palliative care is appropriate for any client and/or family living with, or at risk of developing, a life-threatening illness due to any diagnosis, with any prognosis, and whenever they have unmet expectations and/or needs and are prepared to accept care, regardless of age

The Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA) defines hospice palliative care as an approach to care that aims to, “Relieve suffering and improve the quality of living, and dying. Such a care approach strives to help patients and families:

- Address physical, psychological, social, spiritual and practical issues, and their associated expectations, needs, hopes and fears;

- Prepare for and manage self-determined life closure and the dying process;

- Cope with loss and grief during the illness and bereavement” (Ferris et al., 2002, p. 17).

Palliative Care objectives are:

- Encompass the care of the whole person, including his/her physical, psychological, social, spiritual and practical needs

- Ensure that care is respectful of human dignity

- Support meaningful living as defined by the individual

- Tailor care planning to meet the individual’s goals of care

- Recognize the individual with life-limiting disease and his/her family as the unit of care

- Support the family to cope with loss and grief during the illness and bereavement periods

- Respect the individual’s personal, cultural and religious values, beliefs and practices in the provision of care

- Value ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, truthfulness and confidentiality

- Recognize the individual as autonomous, who has a right to end of life care and to make decisions regarding his/her care to the degree he/she desires

- Recognize the importance of a collaborative inter professional team approach to care, and also recognizes the efforts of non-health-care professionals (e.g. volunteers, faith leaders)

4. Interdisciplinary Care

The number of people dying at home or in long-term care settings is also increasing. Only a small proportion of people actually receive end of life care in specialized settings and the vast majority of these people die from advanced cancer (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007). Although individuals with frailty and noncancerous life-limiting illnesses could benefit from end of life care, clinicians are faced with such challenges as identification of the terminal phase of the disease, changing symptoms, and a short period of active dying (Doyle, Hanks, & MacDonald, 1993; Plonk & Arnold, 2005). Improving education on the signs of impending death and integrating the palliative philosophy of care earlier in the disease trajectory, are strategies that could improve care of individuals living with life-limiting illnesses across health-care settings.

Due to the frequency of interactions with individuals, nurses are likely to be the first health-care professionals to recognize that the person is reaching the last days and hours of life. It is at this pivotal time that nurses can make a significant contribution to the life of an individual nearing death and to his/her family before, during, and after death

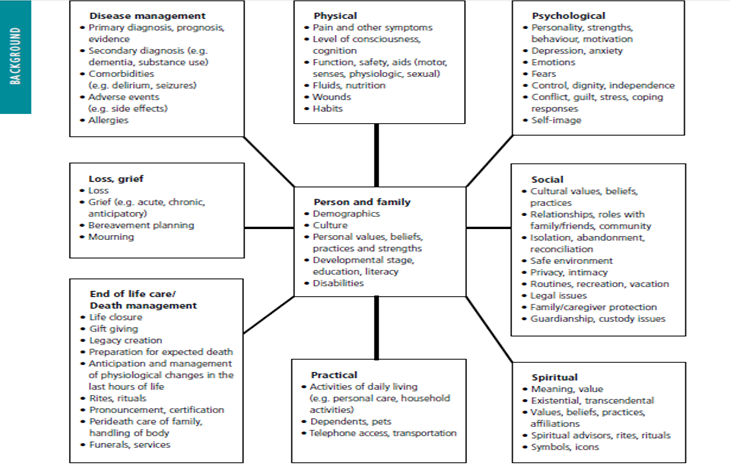

Nurses are not the only care provider since there are many issues associated with illness and bereavement:

- Disease management issues;

- Physical issues;

- Psychosocial issues;

- Spiritual issues;

- Care giving and practical issues;

- End of life and death management issues;

- Loss and grief issues

5. Components of a Program for Better Care in the Last Days and Hours

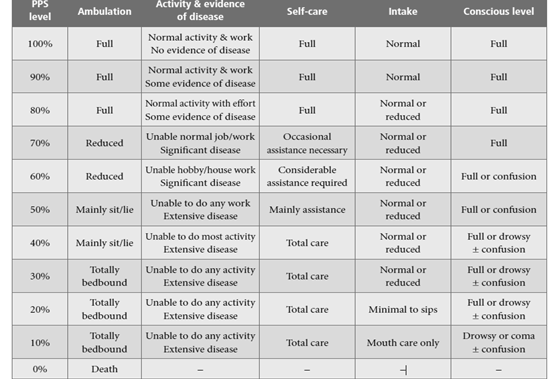

5.1 Tracking & Screening Tools for Estimating Length of Survival for Indificuals at the End of Life

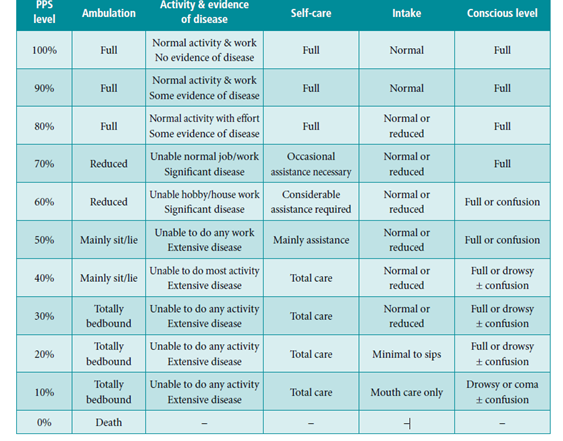

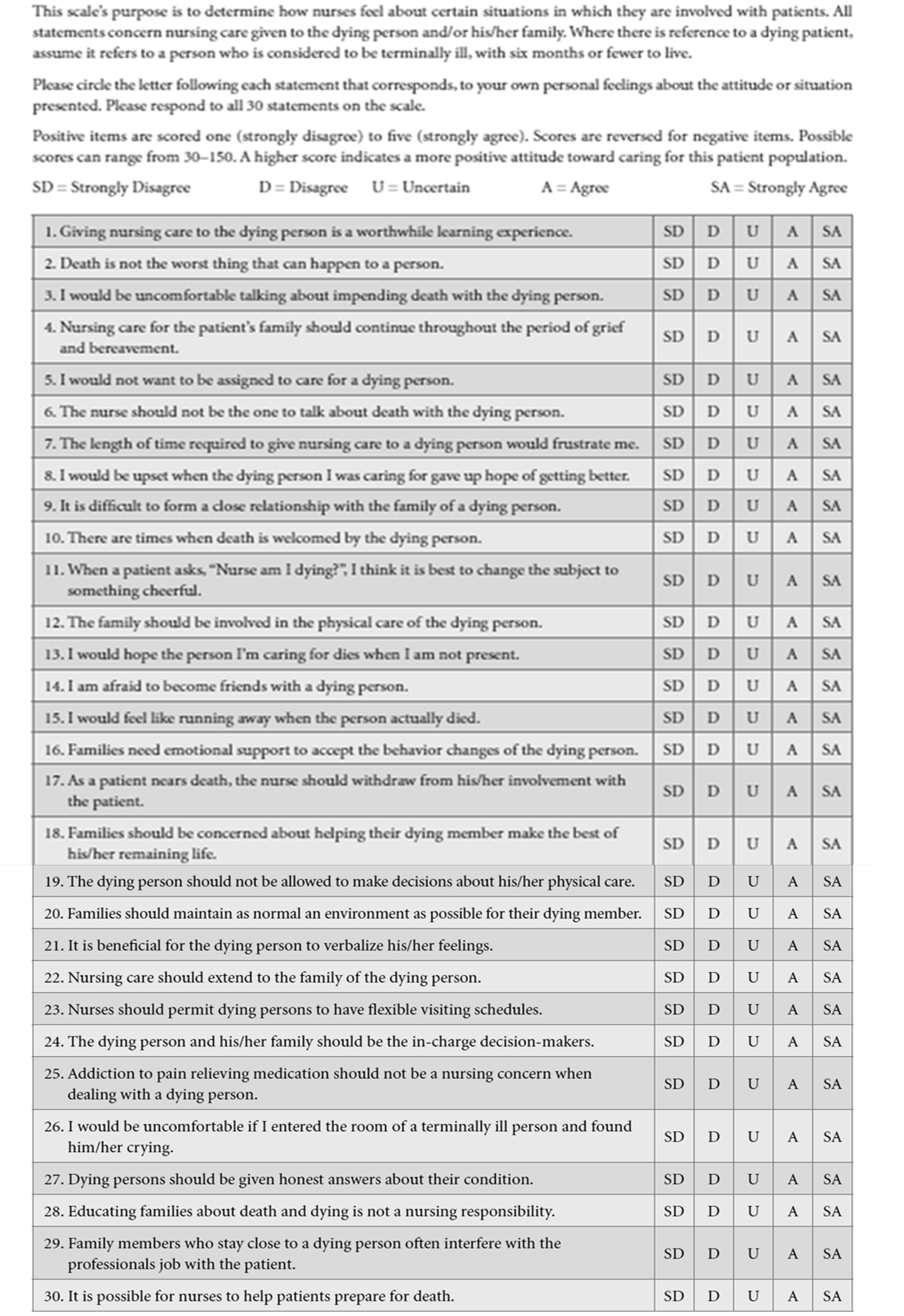

Here are the instructions for Using the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Version 2:

- PPS scores are determined by reading horizontally at each level to find a ‘best fit’ for the patient, which is then assigned as the PPS% score.

- Begin at the left column and read downward until the appropriate ambulation level is reached; then read across to the next column and downward again until the activity/evidence of disease is located. These steps are repeated until all five columns are covered before assigning the actual PPS for that patient. In this way, “leftward” columns (columns to the left of any specific column) are ‘stronger’ determinants and generally take precedence over others.

Example 1: A patient who spends the majority of the day sitting or lying down due to fatigue from advanced disease and requires considerable assistance to walk even for short distances, but who is otherwise fully conscious with good intake would be scored at PPS 50%.

- PPS scores are in 10% increments only. Sometimes, several columns are easily placed at one level, but one or two which seem better at a higher or lower level. One then needs to make a ‘best fit’ decision. Choosing a “half-fit” value of PPS 45%, for example, is not correct. The combination of clinical judgment and “leftward precedence” is used to determine whether 40% or 50% is the more accurate score for that patient.

- PPS may be used for several purposes. First, it is an excellent communication tool for quickly describing a patient’s current functional level. Second, it may have value in criteria for workload assessment or other measurements and comparisons. Finally, it appears to have prognostic value.

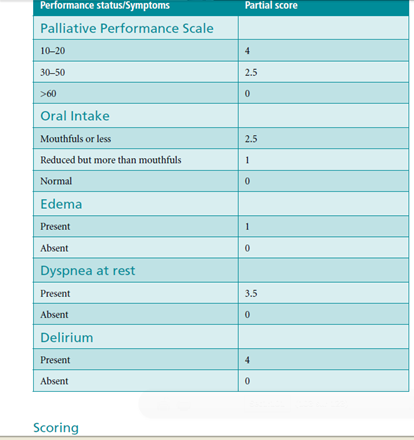

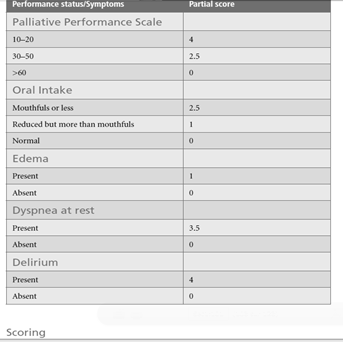

Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI)

The PPI relies on the assessment of performance status using the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS, oral intake, and the presence or absence of dyspnea, edema, and delirium).

Scoring will provide the prognosis (Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Vol. 35, No. 6, Stone, C., Tierman, E., & Dooley, B., Prospective Validation of the Palliative Prognostic Index in Patients with Cancer, 617–622, Copyright (2008)):

- PPI score > 6 = survival shorter than 3 weeks

- PPI score >4 = survival shorter than 6 weeks

- PPI score <4 = survival more than 6 weeks

Clinical Indicator of Decline

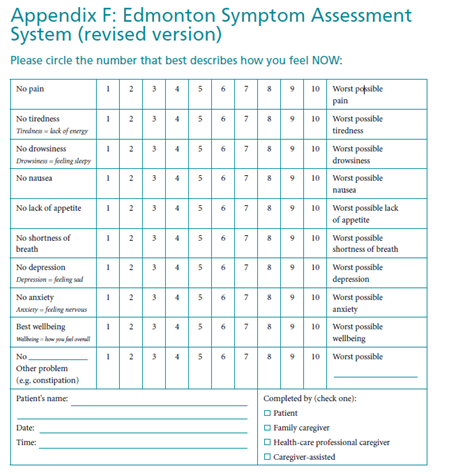

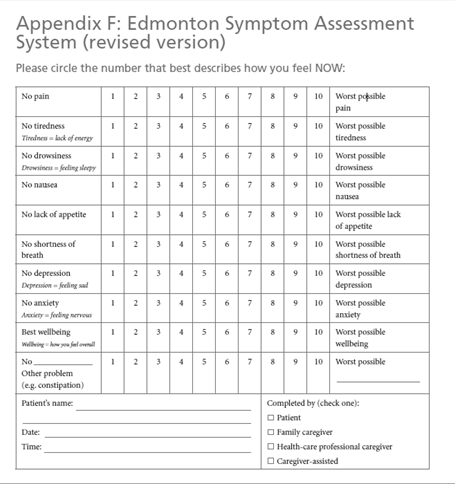

The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) can monitor the overall clinical situation.

General indicators of poorer prognosis (life expectancy of only weeks to many weeks) include poor performance status, impaired nutritional status and a low albumin level.

Diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure run a more fluctuating course and result in death in a less predictable timeframe than diseases such as renal disease or dementia. Each exacerbation can lead to remission (and future exacerbation) or death; knowing which will occur on any given admission is extremely challenging.

Here are some clinical indicators for less than 6 months life expectancy:

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Less than 6 months of life expected:

- Disabling dyspnea at rest, unresponsive to bronchodilators, resulting in decreased functional activity, bed to chair existence, often exacerbated by other debilitating symptoms such as fatigue and cough;

- FEV1 after bronchodilators <30%;

- Increased visits to emergency department/hospital for pulmonary infections and/or respiratory failure;

- Pulmonary hypertension with cor pulmonale/right heart failure;

- 24-hour home oxygen with pO2 <50 mmHg and/or pCO2 > 50mmHg and documented evidence of cor pulmonale;

- Oxygen saturation <88% with supplementary oxygen.

- Unintentional weight loss >10% over preceding 6 months.

- Resting tachycardia >100/min.

Congestive heart failure

< 6 months of life expected:

- Chest pain, dyspnea at rest or minimal exertion and already optimally treated with diuretics and vasodilators;

- Congestive heart failure >2 hospitalizations in the year;

- 50% increase in dose of oral medication or adding new class of drug;

- Left ventricular ejection fraction <20%;

- Creatinine >350 μmol/L.

Only a few weeks remaining:

- History of cardiac arrest and resuscitation.

- History of unexplained syncope.

- Resistant dysrhythmias.

- Hypertension.

- Insulin-dependent diabetes.

- Nicotine use.

- Prior coronary artery bypass.

Dementia

A Month to several months of life expected (all predictors should be present):

- Mini-Mental State Examination <12.

- Unable to ambulate without assistance.

- Unable to dress without assistance.

- Unable to bathe without assistance.

- Urinary and fecal incontinence.

- Unable to speak or communicate meaningfully.

- Unable to swallow.

- Increasing frequency of medical complications (e.g. aspiration pneumonia, urinary tract infections, decubitus ulcers).

Renal disease

Weeks to several month of life expected:

- Creatinine clearance < 10cc/min (<15cc/min for diabetics.

- Serum creatinine > 700 μmol/L ( >530 μmol/L for diabetics)

- Confusion and/or obtundation (less than full mental capacity)

- Intractable nausea and vomiting

- Generalized pruritus

- Restlessness

- Oliguria (urine output <40cc/24 hr)

- Intractable hyperkalemia (>7 mmol/L)

- Intractable fluid overload

Stroke

Days to weeks of life expected:

- During the acute phase any of the following:

- Coma beyond three days duration and dense paralysis

- Comatose patients with any four of the following on day 3:

- Abnormal brain stem response

- Absent verbal response

- Absent withdrawal response to pain

- Serum creatinine >130 μmol/L

- Age >70

- Imaging findings such as:

- Large hemorrhage, with ventricular extension

- Midline shift >1.5 cm or bi-hemisphere infarcts, cortical and subcortical infarcts

- Basilar artery occlusion

5.2 EOL Program and its Components

Assessment at the End of Life

- Nurses identify individuals who are in the last days and hours of life.

- Use clinical expertise, disease specific indicators and validated tools to identify these individuals.

- Understand the end-of-life trajectories.

- Nurses understand the common signs and symptoms present during the last days and hours of life.

- Common signs of imminent death, may include, but are not limited to:

- Progressive weakness;

- Bedbound state;

- Sleeping much of the time;

- Decreased intake of food and fluid;

- Darkened and/or decreased urine output;

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia);

- Delirium not related to reversible causes;

- Decreased level of consciousness not related to other causes;

- Noisy respiration/ excessive respiratory tract secretion;

- Change in breathing pattern (Cheyne-Stokes respiration, periods of apnea); and

- Mottling and cooling extremities.

- Nurses complete a comprehensive, holistic assessment of individuals and their families based on the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association Domains of Care, which include the following:

- Disease management;

- Physical;

- Psychological;

- Spiritual;

- Social;

- Practical;

- End-of-life care/ death management; and

- Loss, grief.

- Include information from multiple sources to complete an assessment. These may include proxy sources such as the family and other health-care providers.

- Use evidence-informed and validated symptom assessment and screening tools when available and relevant.

- Reassess individuals and families on a regular basis to identify outcomes of care and changes in care needs.

- Communicate assessments to the inter-professional team. (See Annex 2)

- Document assessments and outcomes.

- Common signs of imminent death, may include, but are not limited to:

Nurses:

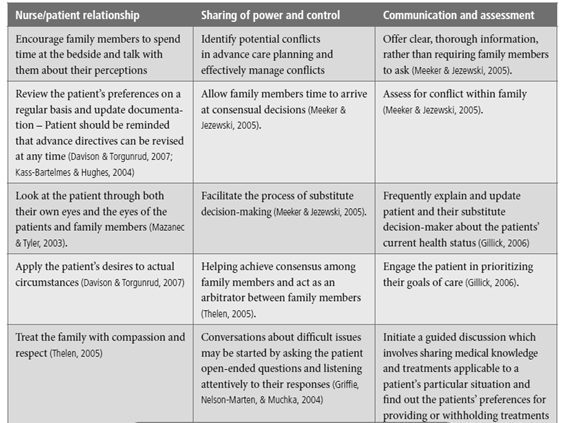

- Reflect on and are aware of their own attitudes and feelings about death (See Annex 3)

- Assess individuals’ preferences for information

- Understand and apply the basic principles of communication in end of life care

- Communicate assessment findings to individuals (if possible and desired) and the family on an ongoing basis

- Educate the family about the signs and symptoms of the last days and hours of life, with attention to their: faith and spiritual practices; age-specific needs; developmental needs; cultural needs

- Evaluate the family’s comprehension of what is occurring during this phase

Decision Support at the End of Life

- Nurses recognize and respond to factors that influence individuals and their families’ involvement in decision-making.

- Nurses support individuals and families to make informed decisions that are consistent with their beliefs, values and preferences in the last days and hours of life.

Care and Management at the End of Life

- Nurses are knowledgeable about pain and symptom management interventions to enable individualized care planning.

- Nurses advocate for and implement individualized pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic care strategies.

- Nurses use effective communication to facilitate end of life discussions related to:

- Reconciliation of medications to meet the individual’s current needs and goals of care;

- Routes and administration of medications;

- Potential symptoms;

- Physical signs of impending death;

- Vigil practices;

- Self-care strategies;

- Identification of a contact plan for family when death has occurred; and

- Care of the body after death.

- Nurses educate and share information with individuals and their families regarding:

- Cultural and spiritual values, beliefs and practices;

- Emotions and fears;

- Past experiences with death and loss;

- Clarifying goals of care;

- Family preference related to direct care involvement;

- Practical needs;

- Informational needs;

- Supportive care needs;

- Loss and grief; and

- Bereavement planning.

5.3 Model for Quality Palliative Care

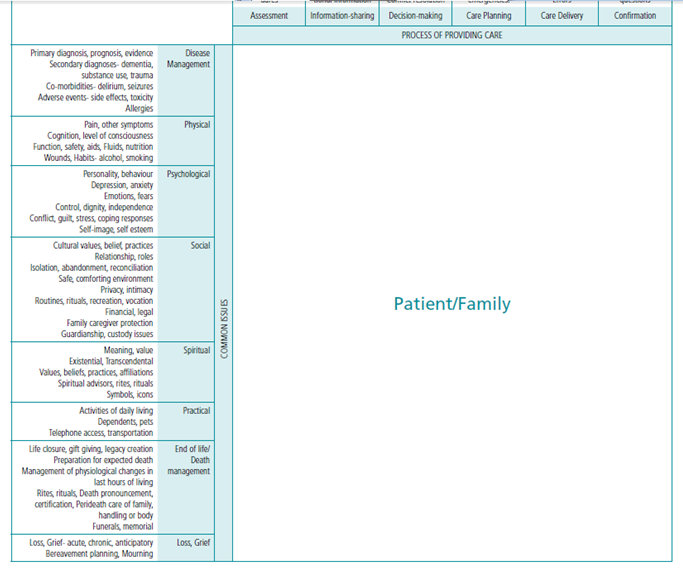

According to Ferris, FD., Balfour, HM., Bowen, K., Farley, J., Hardwick, M., Lamontagne, C., Lundy, M., Syme, A. West, P (2002) . A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association,), a client-family square can ensure quality care. See Figure 1)

The components of the model called “client-family square ae presented in Annex 4

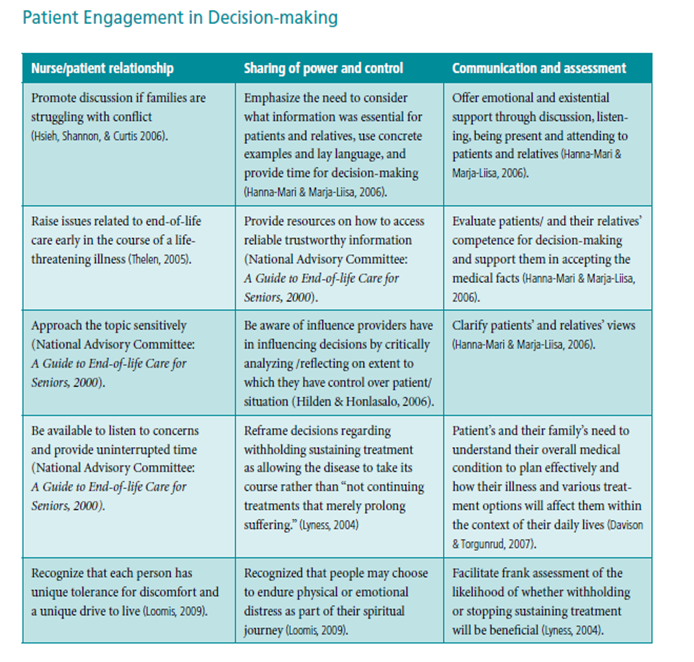

Strategies to help individuals engage in decision-making at the end of life are outlined in the following tables:

5.4 End of Life Care During the Last Days & Hours - Nursing

Nurses Communicate the goals of care and treatment by:

- Using professional judgment to determine how the inter-professional team needs to be involved in discussions about the client’s end-of-life care wishes

- Assessing whether the client has sufficient and relevant information to make an informed decision17 about treatment and end-of-life care, including resuscitation

- Providing an opportunity to discuss, identify, and review the client’s end-of-life care wishes

- Identifying the client’s wishes about preferred treatment and/or end-of-life care as early as possible, while considering the client’s condition and the degree to which the therapeutic nurse client relationship has been established

- Identifying and using appropriate communication techniques when discussing treatment and end-of-life issues with the client

- Helping and being involved in client and family discussions about treatment and/or end-of-life care

- Consulting with other health care team members as required, to identify and resolve treatment and/or end-of-life care issues. (For example, a nurse could present a client situation during a team meeting or rounds or include an ethicist on the care team, if it is appropriate)

- Knowing the end-of-life care wishes of the client or obtaining that knowledge from:

- The client’s direct instructions (which include non-verbal means)

- The client’s advance directive (such as a living will or power of attorney for personal care)

- The substitute decision-maker’s instructions, if the client is incapable, or

- Documented instructions from another member of the health care team

- Explaining the client’s wishes to all members of the inter-professional care team

- Maintaining records of client and inter-professional team communications about treatment and end-of-life care decisions according to organizational policies and procedures as well as the Wales Home’s Documentation practice document

- Contributing to ongoing communication about end-of-life care wishes and implementing the client’s wishes by:

- Reviewing the client’s plan of treatment including resuscitation wishes as needed or when required by organizational policy. (For example, in long-term care settings, the review could be part of the regular client health review)

- Documenting the relevant information

- Communicating any changes in client’s wishes to the inter-professional team and ensuring the wishes are included in the plan of treatment

- Advocating for the creation or modification of practice-setting policies and procedures to support client choices during treatment and end-of-life care, based on Wales Home documents.

Nurses implement a client's treatment and end-of-life care wishes by:

- Ensuring that the creation of the plan of treatment has involved both the inter-professional team and the client, and that the client has given informed consent for the plan of treatment before implementation;

- Acting on behalf of the client to help clarify the plans for treatment when:

- The client’s condition has changed and it may be necessary to modify a previous decision

- The nurse is concerned the client may not have been informed of all elements in the plan of treatment, including the provision or withholding of treatment

- The nurse disagrees with the physician’s plan of treatment

- The client’s family disagrees with the client’s expressed treatment wishes

- Initiating treatment when:

- The client’s wish for treatment is known through a plan of treatment and informed consent

- The client’s wish is not known, but a substitute decision-maker has provided informed consent for treatment, or

- It is an emergency situation, there is no information about the client’s wish, and a substitute decision-maker is not immediately available

- Not initiating treatment that is not in the plan of treatment, except in emergency situations, when:

- The client has not given informed consent, and/or the plan of treatment does not address receiving the treatment

- The incapable client’s wish is not known, and the substitute decision-maker has indicated that he or she does not want the client to receive the treatment

- The attending physician has informed the client that the treatment will be of no benefit and is not part of the plan of treatment that the client has agreed to. In this situation, the nurse is not expected to perform life-sustaining treatment (for example, resuscitation), even if the client or substitute decision-maker requests it, or

- The client exhibits obvious signs of death, such as the absence of vital signs plus rigor mortis and tissue decay

- Documenting in a written plan of treatment all information that is relevant to the implementation of the client’s wishes for treatment at end of life

- Following the client’s wish for no resuscitation even in the absence of a physician’s written do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order

- Engaging in the following when a client’s death is expected or unexpected:

- Identifying whom to notify when the client dies

- Identifying the most appropriate category of health care provider to notify the family

- Identifying the client’s and family’s cultural and religious beliefs and values about death, and management of the body after death

- Identifying whether the family wants to see the body after death

- Documenting according to policies and procedures

- Possessing the knowledge, skill and judgment to determine that death has occurred

- Deciding, if necessary, the category of health care provider that will pronounce the death

- Recognizing that all nurses have the authority to pronounce death when clients are expected to die and their plan of treatment does not include resuscitation. While RNs and RPNs do not have the authority to certify death in any situation, Nurse Practitioners do have the authority to certify an expected death, except in specific circumstances

- Advocating for the creation or modification of practice-setting policies and procedures on the implementation of clients’ treatment and end-of-life care wishes that are consistent with College

Summary of Steps in Advance Care Planning

- Think about your own values and wishes.

- Consult people who can provide advice and guidance, such as your doctor, lawyer, or faith leader.

- Think about the people that you trust to make personal care decisions on your behalf, in accordance with your wishes.

- Decide who your substitute decision-maker should be.

- Appoint your substitute decision-maker to act for you, if necessary.

- Make your care wishes clear to your substitute decision-maker and others close to you.

- If your care wishes change, let your substitute decision-maker know. Revise any written or taped instructions.

- Fill out and carry with you the wallet card provided in this booklet to identify your substitute decision-maker and tell others how to reach them if needed.

6. Form

The form here attached in Annex 5 will be used.

The Annex 6 is providing guidelines for psychosocial care.

7. Responsibilities

- NURSE CASE MANAGER

- Needs assessment, coordination and authorization of services to support the client and family in an appropriate care setting

- Authorization of VIHA Home Support Workers based on client need

- REHAB: OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY / PHYSIOTHERAPY staff

- Functional assessment of mobility, safety and equipment needs to safely remain at home

- Arrange equipment loans such as hospital bed

- DIETITIAN (if available)

- Assess, review and support for dietary issues, including enteral nutrition need and impaired swallowing

- Support care team with symptom management e.g. nausea, cachexia and dehydration towards the end of life

- SOCIAL WORKER

- Family conflict resolution

- Assist with legal documentation, and support client/family with EOL paperwork

- Support with Advance Care Planning, Living Wills and bereavement issues

Conclusion

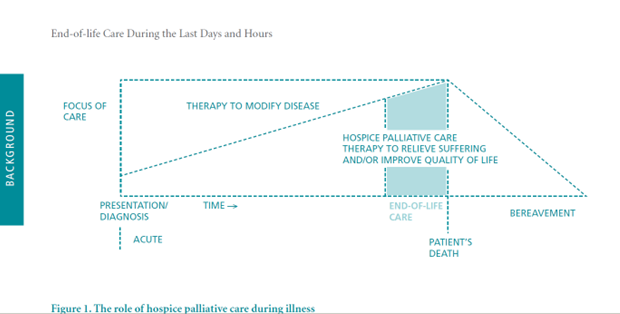

Palliative care focuses on helping people with a life-limiting illness live well day to day. It includes care for the person and his/her family. Palliative care can be given at the same time as treatment to cure or control disease. End-of-life care is a part of palliative care that occurs during the last days and hours of life. Palliative care continues beyond a person’s death to support family and friends during bereavement. This is shown in the diagram adapted from: Ferris, FD. Balfour, HM. Bowen, K., Farley, J., Hardwick, M., Lamontagne, C., Lundy, M., Syme, A. West, P. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2002. Palliative care can be provided by all of the members of your health-care team, and may also include volunteers, spiritual care providers and other members of your community.

Palliative care aims to:

- Relieve pain and other distressing symptoms.

- Help you to be involved in decisions about your care and treatment.

- Work with you to solve problems.

- Provide emotional support.

- Assist you in finding information and resources.

- Support your family during the illness and after death.

Bibliography

- Lynn’s ((2001) Journal of the American Medical Association, 2001, Vol. 285, Issue 7, 925-932

- Ferris, FD., Balfour, HM., Bowen, K., Farley, J., Hardwick, M., Lamontagne, C., Lundy, M., Syme, A. West, P. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2002.

- Victoria Hospice Society, BC, Canada (2001), victoriahospice.org.

Refernces

- http://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/endoflife-care-during-last-days-and-hours

- http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/End-of-Life_Care_During_the_Last_Days_and_Hours_0.pdf

- http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Toolkit_2ed_French_with_App.E.pdf

- victoriahospice.org/sites/default/files/pps_english.pdf

- Guidelines Department of Health, National Health Service, United Kingdom. (2008). End of life care strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_086277

- .Health Canada. (2000). A guide to end-of-life care for seniors. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/H88-3-31-2001-3E.pdf

- .National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2004). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5058

- .Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2008). Palliative care: Recognizing eligible patients and starting the discussion. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://www.effectivepractice.org/site/ywd_effectivepractice/assets/pdf/2a_GAC_2A_-_PALL07_Improving_Care_Planning.pdf

- Caritas Health Group; Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guideline Committee. (2006). Palliative sedation. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://K\DATA\RPCProgramBinder\Section3Clinical\3AGuidelines\3A6PalliativeSedation.doc.

- Department of Health, National Health Service, United Kingdom. (2008). End of life care strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_086277.

- Health Canada. (2000). A guide to end of life care for seniors. Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/H88-3-31-2001-3E.pdf.

- Ian Anderson Continuing Education Program, University of Toronto. (2005). End of life decision making. Retrieved June 16, 2011, from cme.utoronto.ca/endoflife/End-of-Life%20Decision-Making.pdf

- Institute for Clinical System Improvement. (2009). Palliative care (guideline). Retrieved June 16, 2011, from icsi.org/home/palliative_care_11918.html

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. (2008). Health care guideline: Palliative care, 2nd edn. Retrieved June 15,2011, from icsi.org/guidelines_and_more/gl_os_prot/other_health_care_conditions/palliative_care/palliative_care_11875.html.

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services & Missouri End of Life Coalition’s End of Life in the NursingHome Task Force. (2003). Guidelines for end of life care in long-term care facilities. Retrieved June 17, 2011, from http://health.mo.gov/safety/showmelongtermcare/pdf/EndofLifeManual.pdf.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2003). Advanced cancer and palliative care: Treatment guidelines for patients.Retrieved June 15, 2011, from cancer.org/downloads/CRI/F9643.00.pdf.

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2004). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care.Retrieved June 15, 2010, from http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5058.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004). Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer.[Online] http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/csgspmanual.pdf

- Ngo-Metzger, Q., August, K., Srinivasan, M., Liao, S., & Meyskens, F. (2008). End of life care: Guideline for patientcentered communication. American Family Physician, 77, 167–174.

- NSW Department of Health (2005). Guideline for end of life care and decision-making. Retrieved June 16, 2011, from http://www.cena.org.au/nsw/end_of_life_guidelines.pdf

- Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2008). Palliative care: Recognizing eligible patients and starting the discussion.Retrieved June 15, 2011, from http://www.effectivepractice.org/site/ywd_effectivepractice/assets/pdf/2a_GAC_2A_-_PALL07_Improving_Care_Planning.pdf

- Qaseem, A., Snow, V., Casey, D., Cross, T. and Owens, D. (2008). Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians.Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(2), 141-146.

- Symptom Assessment and Management Tools/Resources Tool Website address Brief Pain Inventory

- ohsu.edu/ahec/pain/paininventory.pdf

- Care Search, Palliative Care Knowledge Network

- caresearch.com.au

- Common Signs and Symptoms During the Last Days of Life cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/lasthours/HealthProfessional/page3

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

- cancer.gov/cancertopics/cam

- Edmonton Symptom Assessment System

- palliative.org/PC/ClinicalInfo/AssessmentTools/ESAS.pdf

- FICA (Faith, Importance, Community Address) Spiritual Assessment Tool

- hpsm.org/documents/providers/End_of_Life_Summit-FICA_References.pdf

- Fraser Health Hospice Palliative Care Symptom Guidelines fraserhealth.ca/professionals/hospice_palliative_care/

- Symptom Assessment and Management Tools cancercare.on.ca/cms/One.aspx?portalId=1377&pageId76967

- Collaborative Care Plans

- cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=13618

- The Victoria Hospice Society’s Palliative Performance Scale cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=13380

- World Health Organization Pain and Analgesic Ladder chcr.brown.edu/pain/FASTFACTS3.pdf

- who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/

- AP Educational ResourcesPENDICIES

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing- The Principles and Practice of Palliative Care Nursing and Palliative Care Competencies for Canadian Nurses

- casn.ca/en/Whats_new_at_CASN_108/items/81.html

- Canadian Virtual Hospice

- virtualhospice.ca

- Edmonton Palliative Care Program

- palliative.org

- End of Life Curriculum Project

- http://endoflife.stanford.edu/eol_toolbox/intro_eol_toolbox.html

- End of Life Nursing Education Consortium

- aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC

- International Hospice Institute and College

- hospicecare.com

- Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care (LEAP)Education

- pallium.ca

- National Action Planning Workshop on End-of-life Care

- hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/pubs/palliat/2002-nat-planpalliat/index-eng.php

- Health-care Professional End-of-life Educational Resources and Programs

- http://palliative.info/pages/Education.htm

- Promoting Excellence in End-of-life Care

- promotingexcellence.org

- Toolkit for Nurturing Excellence at End-of-life Transition

- tneel.uic.edu/tneel.asp

- Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End-of-Life Care

- chcr.brown.edu/pcoc/toolkit.htm

Note: The masculine form is used herein merely for the sake of brevity; it encompasses both men and women.

The Résidence Wales Home and CHSLD Wales Inc. shall herein be referred to as the Wales Home.

Annex 1

Terminology

- Actively Dying or Imminently Dying: A prognosis of death is expected to occur within hours to days.

- Advance Care Planning: A process that involves understanding, reflection, communication, and discussion between a patient and their family/health-care proxy for the purposes of prospectively identifying a surrogate, clarifying preferences and developing an individualized plan of care as the end of their life nears. Advance care planning establishes a set of relationships, values, and processes for approaching end of life decisions, and is specific to a patient’s goals and values, age, culture, and medical conditions. The focus of advance care planning is not merely death and the right to refuse treatment, but rather about living well and defining good care as a patient nears the end of life.

- Bereavement: The entire experience of family members and friends in the anticipation of death, the death itself, and the subsequent adjustment to life surrounding the death of a loved one.

- Complementary Therapies: An independent healing outside the realm of conventional medical practice and theory It focuses on the following: the whole person as a unique individual; the energy of the body and its influence on health and disease; the healing power of nature and the mobilization of the body’s own resources to heal itself; and the treatment of underlying causes, rather than symptoms, of disease Examples of complementary therapies include therapeutic touch massage, aromatherapy, music therapy, or biofeedback.

- Delirium: A mental disturbance that is sudden in onset and usually fluctuates, which is characterized by confusion, disordered speech, and hallucinations.

- End of Life: There is no exact definition of end of life; however, evidence supports the following components: (1) the presence of a chronic disease(s) or symptoms or functional impairments that persist but may also fluctuate; and (2) the symptoms or impairments resulting from the underlying irreversible disease require formal (paid, professional) or informal (unpaid) care and can lead to death. Older age and frailty may be surrogates for life-threatening illness and comorbidity; however, there is insufficient evidence for understanding these variables as components of end of life.

- End of life Care. For the purpose of this practice document, the term end of life care refers to the care that is provided to a client at the end of his or her life. The goal of end of life care is to improve the quality of living and dying, and minimize unnecessary suffering. It encompasses the physical, spiritual, social, psychosocial, cultural, and emotional dimensions of client care. While palliative care can be a component of end of life care, end of life care also includes aspects that are beyond the scope of palliative care, such as advance care planning.

- Existential Distress: The experience of life with little or no meaning. It is defined as a state of powerlessness that arises from one’s confrontation with one’s own mortality and results in the consequent feelings of disappointment, futility, and remorse that disrupt one’s engagement with and purpose in life

- Expected Death. For the purpose of this practice document, the term expected death refers to when, in the opinion of the health care team, the client is irreversibly and irreparably terminally ill; that is, there is no available treatment to restore health or the client refuses the treatment that is available.

- Grief: The normal process of reacting to loss. The loss may be physical (e.g. death), social (e.g. divorce), or occupational (e.g. a job). Emotional reactions of grief can include anger, guilt, anxiety, sadness, and despair. Physical reactions of grief can include sleep disturbances, changes in appetite, and physical problems or illness APPENDICIES

- Hospice Palliative Care: An approach to care that aims to “relieve suffering and improve the quality of living and dying. Such a care approach strives to help patients and families: 1) Address physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical issues, and their associated expectations, needs, hopes and fears; and 2) prepare for and manage self-determined life closure and the dying process; and 3) cope with loss and grief during the illness and bereavement.”

- Intractable or Refractory Symptoms: Symptom that cannot be adequately controlled despite aggressive efforts to identify a tolerable therapy that does not compromise consciousness.

- Pain: A state of physical, emotional or mental lack of well-being or physical, emotional or mental uneasiness that ranges from mild discomfort or dull distress to acute, often unbearable, agony. Pain may be generalized or localized.

- Palliative Care: Care that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illnesses. Particular attention is paid to the prevention, assessment, and treatment of pain and other symptoms, and to the provision of psychological, spiritual, and emotional support. Palliative care is guided by the following principles:

- A focus on quality of life, which includes good symptom control;

- A whole person approach, which takes into account the person’s past and current situation;

- Care that encompasses the person with life-threatening illness and their family, friends, and caregivers;

- A respect for the patient’s autonomy and choices (e.g. place of care, treatment options);

- An emphasis on open and sensitive communication (AVERT: Averting HIV and AIDS, n.d).

- Palliative Sedation: The intentional administration of sedative drugs in dosages and combinations required to reduce the consciousness of a terminal patient as much as necessary to adequately relieve one or more refractory symptoms (Palliative Care Network, n.d.).

- Power of Attorney for Personal Care: A legal document that names a substitute decision-maker (called an attorney) and may contain directions about future health-care treatment and issues related to personal care.

- Quality of Life: The ability to enjoy normal life activities.

- Spirituality: An ultimate reality or transcendent dimension of the world; an inner path enabling a person to discover the essence of his or her being, or the deepest values and meanings by which people live

- Terminal Restlessness: See “Delirium.”

- Total Pain: A concept that describes pain from physical, psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual perspectives. Under the “total pain” model, pain assessment in people who are dying requires multidimensional assessment that includes the patient’s biomedical, psychological, and psychiatric characteristics, as well as social, family, existential, and spiritual influences.

- Vigil: The practice of being present at the bedside for extended periods of time prior to death.

- What a capable person expresses about treatment, admission to a care facility or a personal assistance service. Wishes may be expressed to a power of attorney, in any written form, oral form, or in any other manner. The most recent wishes a client expresses while he or she is capable prevail over any earlier wishes the client may have given to the power of attorney.

Annex 2

Interdisciplinary & Family Approach

Tips for Conducting a Family Conference are listed below and are adapted from Ambuel B and Weissman DE. Moderating an end-of-life family conference, 2nd Edition. Fast Facts and Concepts. August 2005; 16. Available at: http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastfact/ff_016.htm

- Pre-Conference:

- Clarify conference goals and roles with the health-care team.

- Identify participants (health-care team, individual and family).

- Organize date, time, and location (private space when available).

- Conference with individual capable to make decisions and family if desired:

- Introduce self and others.

- Review meeting goals; clarify if specific decisions need to be made.

- Determine urgency of decision-making.

- Establish ground rules: Each person will have an opportunity to ask questions and express views without interruption. A legal decision-maker will be identified; and the importance of supportive decision-making will be described.

- Review health status:

- Determine what the patient and their family already know: “Tell us what you understand about your current situation.”

- Review current health status.

- Ask individual and family members if they have any questions about the current situation.

- Clarify expectations.

- Clarify beliefs and values to determine what goals are most important to avoid or achieve.

- Discuss practical implications of preferences and expectations (i.e. are goals realistic and achievable?).

- Allow time for private discussion.

- Review and/or set goals of care.

- Conference with substitute decision-maker(s) and others as identified:

- Introduce self and others.

- Clarify role of substitute decision-maker(s) and confirm willingness to participate in decision-making.

- Review meeting goals; clarify if specific decisions need to be made.

- Determine the urgency of decision-making.

- Establish ground rules: Each person will have an opportunity to ask questions and express views without interruption; a legal decision-maker will be identified; and the importance of supportive decision-making will be described.

- Review health status.

- Determine what the substitute decision-maker(s)/family already know: “Tell us what you understand about the individual’s current situation.”

- Review current health status.

- Ask the substitute decision-maker(s) and family members if they have any questions about the current situation.

- Clarify expectations:

- Ask substitute decision-maker(s): “What do you believe the individual would choose if he/she could speak for him or herself?”

- Based on what the substitute decision-maker(s) understand about what the individual would have wanted, ask he/she: “What do you think should be done?”

- Clarify beliefs and values to determine what goals are most important to avoid or achieve.

- Discuss practical implications of preferences and expectations (i.e. are goals realistic and achievable?).

- Allow time for private discussion.

- Review and/or set goals of care.

- Wrap-up:

- Summarize consensus, disagreements, decisions and goals of care.

- Caution against unexpected outcomes.

- Identify family spokesperson for ongoing communication.

- Document in the health care record: who were present, goals of care, what decisions were made, follow-up plan.

- Maintain contact with individual, substitute decision-maker(s), family and health-care team.

- Schedule follow-up meetings as needed.

- Determine unmet needs for information and support.

- Assist the individual/substitute decision-maker(s) to access resources to address unmet needs.

- Reinforce role of substitute decision-maker if applicable.

- Schedule a follow-up conference.

Annex 3

Attitude Towards Care of the Dying

Annex 4

Components of the Client-Family Square

Disease Management

- Primary diagnosis, prognosis, evidence

- Secondary diagnoses- dementia,

- substance use, trauma

- Co-morbidities- delirium, seizures

- Adverse events- side effects, toxicity

- Allergies

- Physical

Physical

- Pain, other symptoms

- Cognition, level of consciousness

- Function, safety, aids, Fluids, nutrition

- Wounds, Habits- alcohol, smoking

Psychological

- Personality, behavior

- Depression, anxiety

- Emotions, fears

- Control, dignity, independence

- Conflict, guilt, stress, coping responses

- Self-image, self esteem

Social

- Cultural values, belief, practices

- Relationship, roles

- Isolation, abandonment, reconciliation

- Safe, comforting environment

- Privacy, intimacy

- Routines, rituals, recreation, vocation

- Financial, legal

- Family caregiver protection

- Guardianship, custody issues

Spiritual

- Meaning, value

- Existential, Transcendental

- Values, beliefs, practices, affiliations

- Spiritual advisors, rites, rituals

- Symbols, icons

Practical

- Activities of daily living

- Dependents, pets

- Telephone access, transportation

EOL-Death management

- Life closure, gift giving, legacy creation

- Preparation for expected death

- Management of physiological changes in last hours of living

- Rites, rituals, Death pronouncement,

- Certification, Peri-death care of family,

- Handling or body

- Funerals, memorial

Loss- grief

- Loss, Grief- acute, chronic, anticipatory

- Bereavement planning, Mourning

Assessment

- History of issues,

- Opportunities, associated expectations,

- Needs, hopes, fears

- Examination- assessment scales,

- Physical exam,

- Laboratory,

- Radiology, procedures

Information-sharing

- Confidentiality

- Limits

- Desire and readiness for information

- Process for sharing information

- Translation

- Reactions to information

- Understanding

- Desire for additional information

Decision-making

- Capacity, Goals of care, Requests for withholding/withdrawing,

- Therapy with no potential for benefit,

- Hastened death,

- Issue prioritization,

- Therapeutic priorities,

- Options

- Treatment choices,

- Consent, Surrogate

- Decision-making

- Advance directives

- Conflict resolution

Care Planning

- Setting of care

- Process to negotiate/Develop plan of care- address issues/opportunities

- Delivery

- Chosen therapies,

- Dependents, backup coverage, respite

- Bereavement care

- Discharge planning

Care Delivery

- Care team composition

- Leadership

- Education, support

- Consultation

- Setting of care

- Essential services

- Patient, family support

- Therapy delivery

- Errors

Confirmation

- Confirmation

- Understanding

- Satisfaction

- Complexity

- Stress

- Concerns, issues, questions

Annex 5 PALEO Form (Systematic Follow-Up)

Palliative Care and End of Life Care During the Last Days and Hours

Assessment form of individuals and their families

|

Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): functional level : |

Score: % |

Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): |

Score: /100 |

|

PALLIATIVE PROGNOSTIC INDEX (PPI): |

Score: |

No CPR form & EOL cart |

No YES |

Systematic follow-up (nurse)

|

|

Findings: Specify (if applicable) |

Not applicable |

Done |

Date |

Initials |

|

Assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

History of issues, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Opportunities, associated expectations, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Needs, hopes, fears |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Examination- assessment scales, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physical exam, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Laboratory, Radiology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Procedures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information-sharing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confidentiality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Limits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Desire and readiness for information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Process for sharing information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reactions to information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Understanding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Desire for additional information |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decision-making |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capacity, Goals of care, Requests for withholding/withdrawing, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therapy with no potential for benefit, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hastened death, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Issue prioritization, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therapeutic priorities, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Options |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment choices, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consent, Surrogate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decision-making |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Advance directives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conflict resolution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Care Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Setting of care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Process to negotiate/Develop plan of care- address issues/opportunities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chosen therapies, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dependents, backup coverage, respite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bereavement care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discharge planning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emergencies. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Care Delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Care team composition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leadership |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education, support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consultation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Setting of care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Essential services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Patient, family support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therapy delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Errors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confirmation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confirmation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Understanding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Complexity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stress |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerns, issues, questions |

|

|

|

|

|

Interdisciplinary Intervention Plan

|

|

Info. sharing |

Decision making |

Care plan |

Care delivery |

Confirmation |

Date |

Initials |

|

Disease Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primary diagnosis, prognosis, evidence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary diagnoses- dementia, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

substance use, trauma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Co-morbidities- delirium, seizures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adverse events- side effects, toxicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allergies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pain, other symptoms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cognition, level of consciousness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Function, safety, aids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fluids, nutrition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wounds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Habits- alcohol, smoking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Psychological |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personality, behavior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Depression, anxiety |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emotions, fears |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Control, dignity, independence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conflict, guilt, stress, coping responses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self-image, self esteem |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cultural values, belief, practices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Relationship, roles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isolation, abandonment, reconciliation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Safe, comforting environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Privacy, intimacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Routines, rituals, recreation, vocation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Financial, legal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Family caregiver protection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Guardianship, custody issues |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spiritual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meaning, value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Existential, Transcendental |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Values, beliefs, practices, affiliations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spiritual advisors, rites, rituals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symbols, icons |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Practical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activities of daily living |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dependents, pets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Telephone access, transportation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EOL-Death management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Life closure, gift giving, legacy creation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Preparation for expected death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of physiological changes in last hours of living |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rites, rituals, Death pronouncement, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Certification, Perideath care of family, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Handling or body |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Funerals, memorial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss- grief |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss, Grief- acute, chronic, anticipatory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bereavement planning, Mourning |

|

|

|

|

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): functional level: %

PALLIATIVE PROGNOSTIC INDEX (PPI): score:

PPI score > 6 = survival shorter than 3 weeks; PPI score >4 = survival shorter than 6 weeks; PPI score <4 = survival more than 6 weeks

Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): score /100

|

Score |

Date |

Signature |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Family & Interdisciplinary conference form

|

Conference |

Findings if applicable (specify) |

Date |

Initials |

|

Meeting goals; clarify if specific decisions need to be made. |

|

|

|

|

Determine urgency of decision-making. |

|

|

|

|

· Establish ground rules: Each person will have an opportunity to ask questions and express views without interruption. A legal decision-maker will be identified; and the importance of supportive decision-making will be described. |

|

|

|

|

Review health status: |

|

|

|

|

· Determine what the patient and their family already know: “Tell us what you understand about your current situation.” |

|

|

|

|

· Ask individual and family members if they have any questions about the current situation. |

|

|

|

|

Clarify expectations. |

|

|

|

|

Clarify beliefs and values to determine what goals are most important to avoid or achieve. |

|

|

|

|

Discuss practical implications of preferences and expectations (i.e. are goals realistic and achievable?). |

|

|

|

|

Review and/or set goals of care. |

|

|

|

|

Conference with substitute decision-maker(s) |

|

|

|

|

Clarify role of substitute decision-maker(s) and confirm willingness to participate in decision-making. |

|

|

|

|

Review meeting goals; clarify if specific decisions need to be made. |

|

|

|

|

Determine the urgency of decision-making. |

|

|

|

|

Establish ground rules: Each person will have an opportunity to ask questions and express views without interruption; a legal decision-maker will be identified; and the importance of supportive decision-making will be described. |

|

|

|

|

Review health status. |

|

|

|

|

Clarify expectations: |

|

|

|

|

Clarify beliefs and values to determine what goals are most important to avoid or achieve. |

|

|

|

|

Discuss practical implications of preferences and expectations (i.e. are goals realistic and achievable?). |

|

|

|

|

Review and/or set goals of care. |

|

|

|

|

Wrap-up: |

|

|

|

|

Summarize consensus, disagreements, decisions and goals |

|

|

|

|

Caution against unexpected outcomes. |

|

|

|

|

Identify family spokesperson for ongoing communication. |

|

|

|

|

Document in the health care record: who were present, goals of care, what decisions were made, follow-up plan. |

|

|

|

|

Maintain contact : individual, substitute decision-maker(s), family |

|

|

|

|

Schedule follow-up meetings as needed. |

|

|

|

|

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

Signature/title |

Date/Time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annex 6

Transitions in Palliative Care

The Palliative performance Scale and Psychosocial Care

Psycho‐social care of dying patients and their families includes emotional, spiritual, and practical support and counselling through the process of dying, death and bereavement. It is a key component of palliative care that becomes increasingly important as the end of life approaches. Indeed hope for healing of family and personal issues often become the priority as hope for a cure for disease disappears. Good psycho‐social care can also support good symptom management.

The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) can be used to predict the timing of specific emotional, social and spiritual challenges and responses for patient and family, as they are tied to physiological changes.

This section presents the key transition points that occur along the continuum of a terminal illness using the PPS through to death and is summarized in the table below. It looks at basic physical changes, emotional, spiritual and communication issues for the patient and family, as well as psychosocial interventions. These include planning for care, teaching, counselling and mediation. Following this expedited table is an expanded description of care implications for the latter half of the palliative journey for both patients and their families (from 50% PPS through to death).

Beginning the Journey PPS 100-90%

Patient is able to live normally with some evidence of disease.

A time of early diagnosis and treatment. Key psycho‐social care considerations:

- Becoming a Patient – entering the unfamiliar world of health care

Interventions ‐ normalize feelings, validate experiences and provide information.

- Receiving the diagnosis – shock, disbelief, denial.

Interventions: clarify patients understanding of the diagnosis, express practical concerns and offer quiet and calm.

- Fear and powerlessness Interventions – address the fears, create opportunities for support, and examine strategies for coping.

- Making critical decisions – patients and family may disagree with treatments.

Interventions – normalize different perspectives and offer support for whatever decisions patient makes.

- Dealing with the impact of treatments Interventions – rebuild self-esteem and accommodate the demands and effects of treatment. Offer peer support, relaxation skills and opportunities for communication.

The Path not Chosen PPS 80-70%

Patient has some normal activity with effort, to reduced activity, to significant disease. Key psycho‐social care considerations:

- A new awareness – recurrence of disease.

Interventions – explore the impact on the patient/family, support their reactions and provide information as needed.

- Family dissonance –Interventions – explore family stresses, their changing roles and new issues.

- Isolation – reduction of activities and social life.

Interventions – help patients and their families identify supportive activities and people in their lives. Offer resources.

- Uncertain time – future uncertain Interventions – help patients understand the emotional and physical fatigue, open opportunities for discussion

- The faces of hope –Interventions – normalize feelings of hope and despair, give understanding that hope can change and identify small hopes, (hopelets)

- Explore spiritual aspects – values, beliefs and rituals

Entering The Unknown PPS 60-50%

Patient is unable to do any work, experiences extensive disease, may see a change in appetite, may be confused. Key psycho‐social care considerations:

- Change in Focus – toward hospice, palliative care. Interventions – highlight patient/family strengths, identify supports/resources.

- Patient/family grief – anticipatory grief

Interventions – allow for exploration of thoughts and feelings, provide opportunities for life review and support the completion of unfinished business.

- Emotions – anger, fear, powerlessness, denial, unpredictable and suppressed emotions. Interventions – listen, normalize feelings, introduce coping strategies, and accept the patient’s feelings.

- Communication Interventions ‐ normalize differences, light and easy conversation and sometimes indirect communication.

- Family issues Interventions – acknowledge conflict, facilitate resolution, protect patient autonomy and cultivate therapeutic relationships between patients/families

The Long and Winding Road PPS 40-30%

Patient is mainly in bed with extensive disease, normal or reduced intake, may be confused. Key psycho‐social care considerations:

- Change in mobility – Interventions – provide outside resources to assist with physical care and educate regarding expectations.

- Dependence and withdrawal – Interventions – social system diminished, some care decisions now revert to the family.

- Developing a death plan – where do they wish to die? Interventions ‐ explore the patient’s wishes about his/her remaining life, provide resources.

- Family stress – caregiver burnout, family dynamics. Interventions – explore feeling and thoughts about care‐giving burnout and facility placement.

- Family grief Interventions – normalize feelings, acknowledge mixed feelings, and allow expressions of joy and sorrow.

- Family fatigue Interventions – evaluate family members eating and sleeping routines, legitimize rest and relaxation. Is respite needed and available?

Watching and Waiting PPS 20-10%

Patient has no activity, intake sips to mouth care only, consciousness is full ‐ to drowsy ‐ to coma. Key psycho‐social care considerations:

- Doing to being – family shifts from doing to being Interventions – encourage people to take regular breaks from the vigil.

- Communication Interventions – tailor communication to fit the patient’s consciousness level; patients may talk of travels, familiar events and places or going on a journey. Delirium, restlessness and hallucinations are some of the most difficult reactions for families to encounter.

- Making decisions – now shifts to the family Interventions – encourage a family spokesman and support decisions. Preparation for death, supply resources.

- Expectations about dying Interventions – explain pre‐death changes in breathing, pulse, color and awareness.

The Parting of the Ways (Death) PPS 0%

Key psycho‐social care considerations (now for family):

- Family reactions – shock, crying, sobbing, anger – varies with culture.

Interventions – stabilize shock and support and normalize reactions; inquire about rituals the family would like to honor

- Nature of death – sudden death, suicide versus expected death

Interventions – communicate and support. May need counseling referrals

- After death details Interventions – may need to wait for out of town family members to arrive. Inform families what to expect as they enter the room and ways to be with their loved one. Explain after death procedures such as pronouncement and removal of the body

Considerations in Psychosocial Care at PPS 50% and Beyond for Patients and Families

- The Patient (at 50% PPS)

- Responses

When the reality of disease sets in, a patient finds that earth‐shattering psychosocial changes and shifts are triggered. The prospect of cure is unlikely. Along with a loss of control and autonomy come shifts in family roles and responsibilities. This is a time of overwhelming and mixed emotions; panic, confusion, fear, resignation, helplessness, hopelessness.

Patients face fears of suffering and dying. Spiritual questions arise about the meaning of life and meaning of death. There is a shift in hopes, dreams and expectations. Patients have a need to continue engaging with life in a meaningful way through activities that have particular value for them, such as, pursuing alternative healing methods, holding on to hope, or maintaining social contacts and relationships.

At this time, the difficulties that arise tend to be based on pre‐existing family style and patterns. Between patient and family there will be differences in grieving process, and issues around dealing with illness or expected death can surface.

- What Helps

Planning and Teaching: Involvement in planning for care, family future, and other issues can help patients maintain areas of control. Decision making about palliative care and symptom management often occurs at this point. Information about supports and resources available [medical, emotional, spiritual, practical], in the time ahead, is helpful at this time.

Counselling: Building a solid, safe relationship is important now, as is information and support to address feelings of being overwhelmed. Offer available resources; ensure beliefs and understanding arc accurate; consult with appropriate team members. Begin to explore what lies ahead. Determine what is predictable and known, and what cannot yet be known; explore fears of dying, of pain and of suffering.

Exploration and validation of feelings and emotions can help to give reassurance and normalize their experience. Life review and reminiscence offer meaning and perspective to present circumstances.

- The Family (at 50% PPS)

- Responses

When the patient is at PPS 50%, the family often are unable to recognize the physical impact on themselves of providing care to the patient. They may be unable to pace themselves, feeling totally responsible, wanting to maintain control, and unaware of the demands of ongoing care. These factors often lead to poor self‐care, especially through poor sleep, nutrition, and lack of exercise.

Similarly to the patient, when reality of the disease sets in, major psychosocial changes and shifts are also triggered within the family. As the prospect of cure is recognized as unlikely, shifts in family roles and responsibilities take on new significance. This is a time of overwhelming, often mixed emotions. Families may be needing information and/or a prognosis but afraid of the answers, feeling unsure and insecure. Despite having fears of the future, they are starting to plan for it. As the focus on the patient’s needs and situation increases, less importance is placed on family members’ own feelings and concerns. They put their own needs on hold, in part to protect the patient.

The impact of the disease may become more apparent to the children in a family, prompting questions, fears, and changes in behavior.

- What Helps

Planning: This is when family need to be talking to the professional caregiving team; to get information about the disease process, to plan for help with care, to coordinate resources. Family conferences are an excellent way to get everyone involved directly discussing concerns, needs and plans.

Teaching: There is a lot of new information to be absorbed during this time; information about resources and care options that are available in the community, the workings of the various systems family must deal with, and self-care issues and approaches. The adults may need information about children’s understanding of illness and their developmental needs; modelling of appropriate attitudes and language may help. Direct support may be appropriate.

Counselling: A number of areas need to be addressed with family. Intense feelings of being overwhelmed by changes in disease and condition may need to be explored and supported. Fear of not knowing what lies ahead and loss of control need to be discussed. The family’s ways of dealing with this new reality [denial, avoidance, hope, and acceptance] need to be acknowledged. The impact on the family and its functioning brought about by changes, needs to be addressed in terms of the dynamics of the family in the present situation.

Care at PPS 30%

- The Patient (at 30% PPS)

- Responses

As the disease progresses and its impact continues to be felt, the patient may experience waves of helplessness and hopelessness. The ability to adjust to the dramatic changes now, the loss of independence and control, will depend on how well the patient was able to accept and move through the psychosocial shifts that occurred at PPS of 50% and 40%.

Concerns about dependency and being a burden to others often arise with the recognition of increasing care needs. The patient can feel emotionally worn out, tired or drained and often experiences increased periods of drowsiness, sleepiness and confusion. They may begin to think about letting go ‐ of life, of the fight, of worries.

Along with this, unresolved concerns can become an emotional burden and there may be a sense of urgency to bring closure to these issues. This is the time when a shift from fearing death to an acceptance of death often occurs for the patient.

At this PPS level, intake will be significantly reduced to small amounts of soft or liquid foods, such as food supplements or a few spoonfuls of soup, ice cream, and yogurt.

The patient’s conversations are often impeded by sleepiness, wandering attention, and lack of focus or energy. Also, the patient may find it hard to discuss their fears or feelings with family due to the family’s usual communication style and boundaries.

At this time, the patient and family may find themselves in very different places along the acceptance‐denial continuum, making communication difficult between them. This is affected by the patient and family having different opinions, concerns or feelings about care, different hopes or expectations, and different information.

The patient is often more familiar with the reality of their disease and its progression than is the family.

- What Helps